Medical school clinical training" width="389" height="260" />

Medical school clinical training" width="389" height="260" /> Medical school clinical training" width="389" height="260" />

Medical school clinical training" width="389" height="260" />

A new law in Missouri will allow medical school graduates who have not completed a residency to practice in underserved areas. They will be able to call themselves “doctor” but will be licensed as “assistant physicians” with significant limitations on their practice. (The first link is to Senate Bill 716, the bill that was passed and signed by the governor. It covers several subjects, so you will need to skip to page 8 to find the portion we’re discussing.)

The Missouri State Medical Association supports the new law and helped draft the original bill. It is designed to address the state’s critical need for primary care physicians – 40% of Missouri’s population lives in underserved areas but only 25% of the state’s physicians practice there, according to a 2009 survey. Underserved areas have high poverty rates, high infant mortality, large senior populations and fewer primary care physicians per capita.

To address this primary care shortage, other states have expanded nurse practitioner scope of practice and allowed pharmacists to give immunizations, but Missouri is the first state to create a new type of practitioner licensing. Chiropractors and naturopaths argue that they, too, are primary care physicians and can help ease the shortage. Fortunately, no one seems to be taking them seriously. (We’ll return to DCs and NDs as PCPs shortly.)

All other states require at least a one-year residency to be eligible for licensing as a physician. Most physicians complete an additional 3-7 years of residency training before going into practice; usually 3 years for primary care family practice doctors, internists and pediatricians. Med school graduates who become assistant physicians are, according to medical ethics expert Dr. Arthur Caplan, “not likely to be the cream of the U.S. crop.” Prime candidates for assistant physicians are those who didn’t get into a residency, got low scores on the U.S. Medical Licensing Examination, foreign med school grads, and some who would simply prefer that role. But Dr. Caplan also thinks we should give the program a chance and expresses optimism that it could work out.

According to Governing magazine:

The total number of residency applicants has exceeded the total number of positions available since the 1980s. In 2014, 29,671 available positions were filled by 28,490 students, but the number of active applicants topped 34,000. About 7,000 of those were non-U.S. citizens who graduated from international schools, and about half of them found residencies.

The American Medical Association, the Association of American Medical Colleges and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) all oppose this type of fast-track licensing. The Missouri Hospital Association and the state’s medical board, which will write the regulations, did not take a position on the bill during the legislative session. The American Association of Physician Assistants also opposes the law, saying it will be confusing to patients.

ACGME board member Rosemary Gibson told Governing :

“On the surface, it looks like a quick fix, but I think it really behooves [policymakers] to do their homework, to understand what it means to have a graduate of a medical school be called doctor, to have prescriptive authority for powerful drugs like narcotics, to accurately dose and treat people,” she said. “Primary care is not simple. If you have a lot of older people living in rural areas, they have a lot of co-morbidities [such as diabetes combined with heart disease].”

Dr. Thomas Nasca, ACGME’s CEO, agrees:

“These are physicians with only rudimentary experience,” he told Medscape Medical News . “In Missouri, without direct supervision, they’d be able to manage patients with complex diabetes, congestive heart failure, arrhythmias, and malignancies. This doesn’t make sense.

“Physicians in the United States are not trained to enter practice upon graduation from medical school,” Dr. Nasca said. “They don’t have the skill sets required for independent practice. It’s a flawed assumption to suggest that novices are prepared to provide clinical care on their own in a rural area where any medical condition could present itself. This isn’t an emotional response. It’s a data driven response to a very bad idea.”

Despite recognizing the need to serve challenged areas, he doesn’t see this as the appropriate remedy. “I don’t underestimate the challenges we face in delivering care to rural populations and the urban poor. But to provide inadequate care is no solution. There is a dramatic difference between a medical school graduate and a doctor trained in a residency program. Why go back to the 1940s when doctors just out of medical school provided care without supervision? The idea that primary care is somehow simple is ludicrous,” Dr. Nasca said.

The Missouri State Medical Society’s general counsel and government relations director Jeffrey Howell strongly disagrees with critics of the law. He told Medscape :

The opposition puzzles me . . . The physician shortage in Missouri is so bad that communities with 2,000 to 5,000 people barely have access to a doctor one day a week. And they share that doctor with 2 or 3 communities. The new rules are no different than those for older doctors who didn’t have to go through a residency program. They just graduated from medical school and began treating patients.

To be eligible for assistant physician licensing, a med school graduate (including graduates of osteopathic medical schools) must successfully complete the first two parts of the U.S. Medical Licensing Exam no more than 3 years after graduation. He must clearly identify himself as an assistant physician, including an ID badge, and may use the title “doctor.” The state medical board will work out continuing education requirements with med schools and primary care residency programs. Rules regarding prescription drugs must be approved by the state pharmacy board and, if controlled substances, also the state health department.

All must have an “assistant physician collaborative practice arrangement” with a fully licensed physician, who can oversee no more than 3 assistant physicians. These arrangements must be written agreements, jointly agreed-upon protocols or standing orders. The arrangements can, but do not have to, include the authority to prescribe certain drugs and the physician can limit the locations where this may occur. Patients at these locations must be notified they have the right to see the licensed physician. If these drugs are controlled substances there are additional requirements.

The assistant physician must practice in the same physical location as the physician for 30 days, longer if he will prescribe controlled substances. After that, they must be within “geographic proximity” of one another. The assistant physician must submit at least 10% of his charts to the collaborating physician every 14 days for review. If controlled substance prescribing is allowed, that jumps to 20%.

The collaborating physician “is responsible at all times for the oversight of the activities and accepts responsibility for primary services rendered by the assistant physician.” However, as long as the licensed physician follows the procedures set forth in the law, he won’t be held vicariously liable.

It is interesting to compare the cautious (but nevertheless controversial) medical approach to granting a limited, supervised primary care scope of practice license to an MD with that of chiropractors and naturopaths. Missouri, by the way, saw naturopathic licensing bills introduced every year but one from 2000-2010. None passed, and naturopaths are not licensed in Missouri. In fact, there is case law holding that a naturopath who diagnosed and treated patients without a license to practice medicine can be enjoined as a public nuisance.

There is a movement among chiropractors to claim they are primary care physicians. (We’ve discussed this before several times on SBM – see here for references to all posts.) Some chiropractors seem to have the term mixed up with “portal of entry,” which means the patient can see a practitioner without a referral. The notion that chiropractors can move beyond musculoskeletal care is not universally shared. It’s not even agreeable to some to move beyond straight subluxation-based practice. This simply reflects the internecine wars that have been going on in chiropractic for years.

The most eager proponents of full-scope primary care practice appear to reside in New Mexico, where the “advanced practice chiropractor,” with a few additional hours of education and a limited formulary, can practice. This has led to some interesting attempts to, shall we say, “specialize” among NM DCs. Fortunately, the legalization of an “advanced practice” DC scope of practice does not appear to have seeped beyond the state borders and we hope it won’t, although that was not for lack of trying elsewhere.

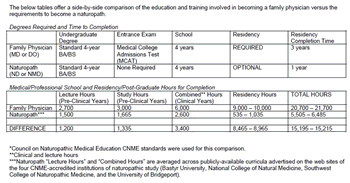

Naturopaths with “naturopathic doctor” degrees seem dead serious about their claim to PCP status, although their latest licensing successes have fallen far short. (Also here.) They even have the audacity to claim that their education and training is “substantially equivalent to” the MD primary care physician. Never mind that a portion of these hours are spent learning pseudoscience, like homeopathy. This led to a misleading chart, handed out to legislators, trying to bend and stretch the two curricula until the chart showed, under torture, supposed similarities. (Chiropractors have attempted similar nonsense. Also here.) The American Academy of Family Physicians apparently took umbrage at these shenanigans, rightly so, and put together its own chart. Using the same basic idea – that number of hours, and not content, is the relevant measure of comparison – the AAFP gave the naturopaths a dose of their own medicine.

AAFP — ND comparison. Click to embiggen.

And so it is we find that the MD assistant physician will have had twice as many hours, including over twice as many clinical hours, as a naturopathic “physician” who goes into practice straight from naturopathic school. Even if the naturopath did a one-year optional residency (most don’t), which can be as few as 535 hours, the naturopath barely squeaks by the MD assistant physician in total hours, and will still have fewer hours than the MD clocked during the clinical portion of his education (the combined clinical and lecture hours of the last two years of med school).

Even without a residency, med students must practice in a variety of clinical settings and put in far more hours of clinical training. Naturopathic students are mostly limited to school-based ambulatory clinics where they see a narrow range of diseases and prescribe fantasy treatments, yet want full PCP scope of practice.

Of course, if you look at a board-certified family practice physician versus a naturopathic “physician,” even one with a residency, the NDs’ comparison becomes a joke. So much for the “equivalent education and training” argument. And if naturopaths would like to go toe-to-toe with the AAFP on actual content, we’d all love ring-side seats.

The contrast between the approaches of MDs/DOs and NDs to the limitations of practicing before education and training meets medical licensing standards is telling.

Whatever you might think of Missouri’s new law, you’d have to agree that any patient is far better off getting primary care from an assistant physician than a naturopath or a chiropractor. Dr. Nasca made the very point I’ve argued before in opposition to ND licensing:

Patients don’t come to primary care physicians sorted into simple problems and complicated problems. . . The idea that primary care is simple and this idea that primary care can be done by people who are not well trained is a flawed concept. It is wrong. The primary care physician, in my opinion, has the most difficult job in the healthcare delivery system. That’s because they must not make errors of omission. They must not make errors of failure to recognize. It is a very challenging task.

Dr. Nasca is absolutely right when he says that “the idea that primary care is somehow simple is ludicrous.” To which we might add: the idea that DCs or NDs can serve as primary care physicians is even more ludicrous.