International trade creates opportunities for nations to cooperate for a higher standard of living. Trade agreements facilitate cross-border trade by lowering tariffs and setting rules on a broad range of issues. But trade agreements also serve as instruments for superpower nations to expand their economic and geopolitical influence. And as inevitable participants of this power struggle, middle powers need to consider not only economic concerns but also diplomatic consequences of joining these trade agreements. This article discusses early trade liberalization, various trade agreements, the U.S.-China conflict, and South Korea as an example of a nation caught in the middle of that conflict.

I. From Multilateral to Bilateral/Plurilateral Agreements

In the early years of trade liberalization, the United States and Europe led the formation of the rules of international trade. Multilateral trade agreements under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and the World Trade Organization (WTO) maintained global trade order. However, WTO negotiations are in an impasse since the Doha Development Round that began in 2001.

As multilateral agreements under the GATT/WTO regime became increasingly difficult to reach, nations started to turn towards bilateral and plurilateral trade agreements. With fewer negotiating parties, bilateral and plurilateral trade agreements with far-reaching clauses could be more readily concluded. These agreements include detailed provisions that not only affect market access but also could potentially shape global rules on a number of non-trade issues, such as environment, labor practices, and state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Given the enhanced geopolitical significance of these trade agreements, foreign and security policies are playing greater roles in states’ decision to pursue trade relations. As a result, trade relationships are becoming more complicated and difficult to balance.

While bilateral and plurilateral trade agreements promote trade liberalization, they could also divide the world into “competing, discriminatory regional trading blocs.” The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) exemplify the competition among the major powers to gain more influence in the global economy.

II. The Power Struggle

On October 5, 12 countries, including the United States, Japan, and Australia, reached an agreement on the TPP, which will account for about 40 percent of the global GDP. The TPP will reduce over 18,000 tariffs and set common standards on issues such as intellectual property, environment, and dispute resolution. Its “open architecture” allows non-party nations to join in the future and gives the TPP a potential of becoming a “de facto template for a new system of rules.”

The United States emphasizes the geopolitical importance of securing a significant bloc of the global trade. President Obama noted, “The TPP means that America will write the rules of the road . . . [and] if America doesn’t write those rules – then countries like China will.” The U.S. Secretary of Defense also stated that the TPP has a geopolitical significance similar to that of an “aircraft carrier” and will “promote a global order that reflects both our interests and our values.”

The United States hopes that China will be forced into accepting the trade rules set by the TPP. The TPP’s strict regulations on SOEs, environment, labor, and intellectual property would require China to significantly reform its economic and legal structure. Instead of accepting the rules formed by the TPP, China is aggressively pushing for its own economic order through the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the RCEP. The AIIB is considered by the Obama administration as China’s effort to counter the U.S.-oriented World Bank, while the RCEP is a China-led regional agreement that embodies “China’s version of global trade.” If concluded successfully, RCEP would be the world’s largest trading bloc, with 16 member nations including Japan, India, South Korea, and the ASEAN nations.

With the TPP, the Unites States plans to contain China and secure a strong U.S. presence in the Asian Pacific. However, the TPP failed to include a few of the most important players in Asia: India, South Korea, and, of course, China. Without the participation of these major Asia Pacific nations, it will be difficult for the United States to gain a “lasting position of supremacy in China’s backyard.”

III. Caught in the Middle: South Korea

Among the nations that did not participate in the founding membership of the TPP, South Korea presents an interesting case. In 2014, South Korea was the sixth largest exporter in the world, and recent statistics show that South Korean products account for considerable global market shares: 37 percent in LCD televisions, 33 percent in cellphones, and 9 percent in automobiles.

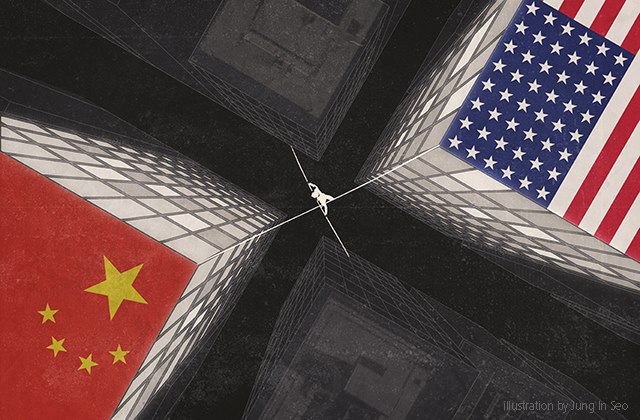

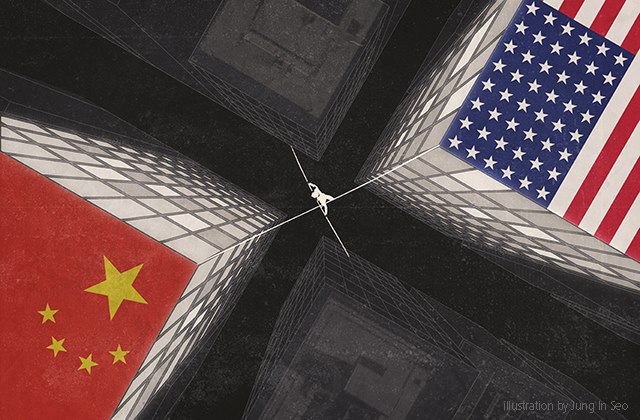

As an active middle power, South Korea wishes to maintain its longstanding U.S.-Korea alliance and build a China-Korea relationship at the same time. But this balance is difficult to achieve due to the intensifying rivalry between the United States and China. Both the United States and China want South Korea on their sides.

South Korea signed on to the RCEP but is hesitating over joining the TPP. In addition to affecting foreign relations for South Korea, the TPP may benefit some domestic industries but hurt others. This tricky situation puts South Korea in a dilemma.

The Korean peninsula has long been central to the conflict between the United States and China. During the Korean War, the United States defended South Korea while China supported North Korea. South Korea still has a strong military alliance with the United States and is considered as “one of America’s closest allies and greatest friends.”

The United States seeks to maintain influence in the Asia Pacific region through considerable military deployments to Asia Pacific countries including Japan and South Korea. Neighboring North Korea and China, South Korea has a great geopolitical importance in U.S. foreign and security policy. As a signal of such significance, almost 30,000 U.S. troops are stationed in South Korea. But the United States’ involvement does not end with the deployment of its troops. Ever since the Korean War, the United States has had wartime operational control of the South Korean military. If a war breaks out, the United States, not South Korea, will have control of the South Korean troops. Although the wartime operation control was to be returned to South Korea in 2012, it is still yet to be transferred.

With such extensive and somewhat paternalistic U.S. involvement, it will be difficult for South Korea to keep ignoring the pressure from the United States to join the TPP. As Nobel Prize winning economist Thomas Schelling mentioned, “Trade is what most of international relations are about. For that reason trade policy is national security policy.”

Future military involvement by the United States is a subject of a heated debate in South Korea, the outcome of which may affect Korea’s trade and foreign policy. Liberals argue for less reliance on the United States, while conservatives oppose such change. If South Korea decides to remain dependent on U.S. military’s support, joining the TPP will help strengthen the U.S.-Korea alliance. If South Korea chooses to rely less on the U.S. military, RCEP could be more valuable than the TPP in terms of regional security. Absent U.S. troops, South Korea may not be able to maintain stability within the peninsula without the help of China, which has the power to keep North Korea in check. A close economic relationship with China through the RCEP and China-Korea Free Trade Agreement (FTA) may help secure that support from China.

B. China Relations

Because China is South Korea’s largest trading partner as well as Asia’s most powerful nation, Seoul has much to lose if it distances itself from Beijing. Especially with China leading the RCEP and AIIB, South Korea may face economic and geopolitical disadvantages if it does not actively participate. Accordingly, South Korea was recently busy pursuing a closer relationship with China through the China-Korea FTA, AIIB, and the RCEP. Commentators noted that South Korea might have refrained from joining the TPP in furtherance of this pursuit. In the past, China-Korea relations used to be described as “cold in politics, hot in economics,” but it is now being labeled as “hot in politics, hot in economics.”

But despite positive developments with China, it is unclear whether South Korea will be able to strike the right balance between the United States and China. The United States remains a close ally of South Korea, and China is disdainful of that relationship. China has viewed the U.S.-Korea alliance as “a remnant of the Cold War system” and “a regional security threat.” Hoping to relieve this tension, South Korea recently proposed the Northeast Asia Peace and Cooperative Initiative (NAPCI).

C. Additional Considerations

Because South Korea already has FTAs with 10 of the 12 members of the TPP, Korean policymakers had thought that the TPP would be redundant and provide no significant geopolitical benefits. In light of the recently revealed full text of the TPP, some commentators argue that South Korea should join while others are hesitant.

The TPP will result in lower trade barriers in several major industries compared to the current FTAs between South Korea and the TPP members. Especially with Japan as a TPP member, South Korea’s electronics and automobile industry may lose competitiveness if South Korea does not join. But a lower trade barrier in the agriculture industry could be detrimental for South Korea. By not participating in the drafting of the TPP, South Korea lost the opportunity to negotiate favorable terms into the agreement.

Private interests will likely influence South Korea’s decision to join the TPP. The TPP is predicted to have disparate consequences for different industries in South Korea. On the one hand, the agriculture and fishery industry as well as state-owned companies will face disadvantages if South Korea joins. On the other hand, the electronics sector will benefit from the TPP because the agreement significantly lowers tariffs on electronics.

South Korea must carefully assess the economic and geopolitical consequences of joining trade partnerships. In attempting to accommodate the wishes of both the United States and China, South Korea may end up weakening relations with both countries. It is a difficult situation. And in the midst of the U.S.-China conflict, South Korea is only one example of the many nations that will have to balance various interests in navigating the complicated global trade relations.

Jisan Kim is a 2017 J.D. candidate at Harvard Law School and a Feature Editor of the Harvard International Law Journal .